In this episode, Google’s director of energy, Michael Terrell, explains the company's new goal of supplying all of its facilities with clean energy 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. We discuss how its going, what kinds of new technologies will be needed, and what new policies could help move things along.

Full transcript of Volts podcast featuring Michael Terrell, April 27, 2022

David Roberts:

One of the big energy stories of the last decade is the surprising scale and vigor of the corporate sector’s push into clean energy. In 2020 alone, US corporate and industrial (C&I) buyers procured 10.6 gigawatts of renewable energy — a third of all the renewables capacity added in the country that year.

One of the earliest and most ambitious buyers was Google, which announced in 2012 that it would set out to procure renewable energy equal to its total energy consumption; it achieved that goal in 2017 (and every year since).

Then, in 2020, Google announced a new goal: it wants to run all of its facilities around the world on carbon-free energy, every hour of every day, 24/7. That is a much more difficult undertaking and it involves much more than wind and solar power. (I did a series of posts/pods on the 24/7 target if you want to dig in deeper.)

Last week, Google released a new white paper in which it makes a series of policy recommendations, from clean energy standards to new regional energy markets, that it argues will help it and the rest of the grid reach round-the-clock clean energy.

It seems like a good occasion to connect with Michael Terrell, Google’s director of energy, to ask him how the 24/7 effort is going, what kinds of technologies might help achieve it, and what sorts of policies could help unlock it for the entire grid.

So without further ado, Michael Terrell from Google. Thanks for coming to Volts.

Michael Terrell:

Thanks for having me.

David Roberts:

Michael, how long have you been with the company? How did you end up here? And what are you in charge of?

Michael Terrell:

I'm a global director of energy at Google. I've been at Google now for more than 14 years, which is a long time. We've been busy during that time building an energy company within Google, and it’s really been a thrill to be part of that journey.

I remember some of our very first projects, years ago, when we were literally taking hybrid Toyota Priuses and converting those into plug-in Priuses; we wanted to test and see how plug-in vehicles would work, because there weren't any available.

I remember when we decided to take on a goal to be 100 percent renewable, annual matched, for our data center energy and thinking at the time, which was probably around 2012, that it would take us two decades to pull that off – and we did it in five years.

So we've really been building this capability around energy within Google, tied to our operations and our data centers. As we're all seeing, the space continues to evolve, and we're making great progress on carbon-free energy. It's enough to keep me interested, and I think it's safe to say that we're still at the beginning of this journey. I think the best is yet to come.

David Roberts:

Google is known for its grandiose aspirations – big, grand, long-term goals. Does it have one of those for energy and sustainability? Is there a North Star that you're working to in the long term?

Michael Terrell:

Certainly on energy, it's 24/7 carbon-free energy. We've also set a net-zero goal as a company, which is to by 2030 achieve net zero across our entire operations and value chain for the company.

But I would also like to think that we can have a much bigger impact in the world and help the world meet this incredible challenge of climate. That's our ultimate goal.

David Roberts:

The idea of a company buying enough renewable energy to offset the amount it used over the course of a year is now an extremely familiar goal, but Google was early to it and early to achieve it.

At this point, I feel like that goal is relatively easy for a company to hit because the market is flooded with cheap wind and solar, and it's not that hard to buy it in bulk. So in 2020, Google announced a new goal, which is not just to buy as much renewable energy as the energy it used, but actually buying renewable energy in the hours it is using energy, i.e. matching its energy use with clean energy purchases on an hour-to-hour basis – so-called 24/7 energy. This is a much bigger and more ambitious goal than just buying renewable energy in bulk.

One way you could approach clean energy procurement as a big company like Google is to reduce the maximum amount of emissions for the dollars you spend – awkwardly known as emissionality. The way you would do that in practice is to buy a bunch of cheap renewables on dirty grids – go to some grid in the Midwest and just keep buying cheap wind and solar. In emissions terms, that's the biggest bang for your buck.

You're not doing that. Instead, you are trying to clean up each individual grid you're on in each individual hour, which, at least in the short term, will have the effect of maybe not reducing as many total net emissions at higher cost. So what is the offsetting benefit of 24/7? What attracted you to it beyond the bulk emissions standpoint?

Michael Terrell:

Keep in mind that 24/7 is about running carbon-free everywhere and at all times. What you're talking about is “let's go find the dirtiest place we can and do renewable energy projects there, and we'll tally up the emissions that we offset and apply that to our footprint.”

All of these methods have their advantages and their disadvantages, but we need a movement to drive a massive transformation in the economy. This is not an accounting exercise; we're trying to decarbonize the global economy. I'm not so sure it's about going off to some far-off place and squeezing additional grams of carbon dioxide reduction out of individual projects. What we need is every company demanding from their utility suppliers, from their local policymakers where they operate, that they need to be run carbon-free, and they need to run carbon-free now.

That's what we're trying to accomplish here. It's not just about making Google run 24/7; we want to make the electricity grids run 24/7, and we want everyone to have a stake in that. Setting this goal that we're going to run carbon-free at all times everywhere that we have operations really gives you a stake in the places where you run that you maybe haven't had before.

Ideally, we want thousands of companies doing this. This can be an incredible engine for change. I'm not saying that the other method is not something that could be effective, because it certainly could, but if you take the long view, and the view of driving entire power grids to carbon-free as fast as possible, having that sort of movement and a push from companies could be super beneficial.

David Roberts:

So the reason it's different than the bulk emissions perspective is because of the intermittency of renewable energy. If you're on, say, an Iowa grid, and you've bought a bunch of wind, there comes a point where buying more wind is not going to cover more hours, because the wind is only blowing when the wind is blowing, and there are hours when the wind is not blowing. Taking this 24/7 perspective means filling the gaps that wind and solar leave behind.

You've divided your approach to doing this into three pillars that proceed from the individual company procurement decision out to broader questions. The first pillar is just transacting for energy. We understand it'll be bulk wind and solar most places, but what in practice are you actually buying to fill those gaps? What's out on the market today that you're transacting beyond wind and solar?

Michael Terrell:

It's a great question. When we set this goal, we weren't really sure what we were going to find out on the market. But once we went public, we found that energy suppliers have come forward with great solutions.

What we've been doing is, instead of going to a solar developer or a wind developer and saying “we want to sign a power purchase agreement for 100 megawatts of solar,” we've gone to energy providers and said “we want to reach 80 or 90 percent carbon-free in this location, can you put together a portfolio of assets that can help us do that?”

We've now done some of these deals. We did a deal with AES for our Virginia data centers where they're packaging a portfolio of new assets – new wind, new solar, storage, some run-of-river hydro – to help us take that site to 90+ percent carbon-free. We've done a similar deal with ENGIE in Germany. So we're seeing these kinds of solutions emerge in the market where we can mix and match resources.

To your point, it's mainly technologies that have already been scaled, so mostly wind and solar, also storage, and we're seeing a little bit of hydro as well. We still have a lot of work to do on some of the newer technologies, but in terms of contracting, we're starting to see more opportunities to mix and match resources, which can really help you push into those higher percentages of carbon-free.

David Roberts:

One of the interesting things about approaching 24/7 as a company is that it's sort of a miniature version of what the whole economy is doing slightly longer term. You're addressing all these challenges that are going to be more widely addressed, first.

One of the big questions about that larger effort is how far we can get with currently commercial technologies – wind and solar, storage to fill most of the gaps, then a little hydro here and there, nuclear where there’s plants running. Have you discovered that you're able to get a little farther with just that stuff than you thought you might be able to? How far can you get with the tools that are currently on the table?

Michael Terrell:

We now have five sites that we've taken to more than 90 percent clean, and there are a few factors that come into play. What are the assets that are already on the grid? Does the grid already have a lot of hydro or nuclear or wind? That's certainly a factor. If your starting point is a 40 percent clean grid, that's a lot better than a starting point that's a 10 percent clean grid. What the state of the grid is and where you're located is a factor.

Then, also, what does the resource look like in that region? Is it a region that has a great solar resource? Is it a region like Iowa that has a great wind resource? Those factors come into play too, how much you can contract for those particular resources.

The biggest factor that we've seen is location. There are a lot of places now in the US where you can get to high penetrations of renewables, and especially if you have a regionalized grid, that's a big factor. Then also, again, is there a strong wind resource or solar resource?

In areas like Singapore or Taiwan, where you're really limited on land and limited in terms of the wind or the solar resource, it's much, much harder. We have found that the regional differentiation is much higher than we would have thought.

David Roberts:

Are there any places where you've been able to get more than 90 percent that might surprise people, or are they more or less where you would expect?

Michael Terrell:

Oregon, Iowa, Oklahoma, Finland, Denmark – I'm not so sure any of those would surprise people. A lot of our sites certainly have that potential, with Asia being the hardest by far.

David Roberts:

In those places, I’m guessing mostly wind and hydro doing the bulk.

Michael Terrell:

Wind, solar, hydro, some existing nuclear as well, especially in the European sites. It's really a mix.

David Roberts:

So that's pillar one: transacting for energy resources that are out there now. Pillar two is technology development, looking ahead at what technologies will be needed to get to this goal in 2030 and doing what you can to push those along.

I have two questions on that. One is, what can a company do? What you’re talking about is basically industrial policy; theoretically, it’s the kind of thing that the US government ought to do, to be paying for R&D and tech development and offering those market push-and-pull policies. But what can a big corporation do to induce technology development in the way you're trying to do? Secondly, what are the most promising, just-over-the-horizon tools that you think are going to help you?

Michael Terrell:

There's no question that we're going to need to see some advancements on the technology side. Wind and solar and storage alone are not going to be enough to get us to 24/7 carbon-free energy or to get a lot of grids around the world to 24/7 carbon-free energy. That's been a big learning, and it's another reason why setting this goal requires you to take a much more holistic approach to how you think about the problem.

There are really two pieces to this: the generation side, which you touched on, but also demand.

On the generation side, yes, we need to find new sources of power generation beyond wind, solar, and storage, or we need to have long-duration storage that you can pair up with those existing assets that will help you get to 24/7. We've been looking at a number of technologies on the generation side – advanced geothermal, hydrogen, carbon capture, nuclear. We've signed a deal with Fervo Energy, out of Texas, that's piloting a new advanced geothermal process, and we're working with them in Nevada right now on a project that would power our data centers in that state that uses some of these advanced geothermal technologies.

What can Google do? We can certainly go to those who are developing these technologies and sign deals to get them piloted or deployed. We're also working on the policy side, because the US DOE has said there are 120 gigawatts worth of new geothermal potential in the United States – how can we tap that asset and really get that to expand and scale? So on the generation side, being an offtaker, sending signals to the market that we’re ready and willing to try these technologies.

The other thing is looking at the capabilities we have as a company. We're a technology company and we have capability around data and compute. We are now using machine learning to manage a large portion of our US wind portfolio, to optimize those wind farms and how they interact with the market; we're actually forecasting the production of wind and bidding those wind farms into the market day ahead, which provides better probability of getting a higher revenue stream and makes those assets more attractive to the market. So we’re using our capabilities around machine learning to make some of these existing resources work better.

Another thing that we're doing is starting to shift the actual loads in our data center, shift our consumption around both in time and in place, to align with the times of the day that the grids are the cleanest.

David Roberts:

How much of your computing load can be moved like that? How much of it is fixed, has to be done in real time, and how much of it is adjustable?

Michael Terrell:

We're still discovering that, because it's early stages. But there are a lot of services – such as storage, or adding new features to Google Photos or other products – that are not necessarily as time sensitive as running a Google search would be, so that the compute can be shifted. We're finding more and more that we maybe have capability to shift more than we thought. It's still early stages on that, but it's a promising development.

It also underscores that to reach 24/7 carbon-free energy, it's not just about finding advanced forms of power generation. You've got to get a lot smarter in managing that dance between generation and demand. So that's something that we're working on now. We've made some promising progress, and we're excited about some of the opportunities that we're seeing.

David Roberts:

On the generation side, everybody's going to want me to ask about small nukes or advanced nukes, whether any of those have struck you as far enough along that you’ve actually offered up some money. Same thing about hydrogen – have you signed any deals with actual projects yet? Are you looking around?

Michael Terrell:

The first public deal that we've done in this area is around advanced geothermal, but we're certainly looking at these other technologies. A lot of progress has been made around hydrogen and nuclear in recent years. There are opportunities with those technologies that we're looking at, so stay tuned. We're at a point right now where we're not taking anything off the table.

David Roberts:

Do you have your eye on thermal storage or anything else in the storage realm?

Michael Terrell:

We're looking at a number of different storage technologies. We already use storage within our data centers; we have signed power purchase deals that involve storage. But this is an area that is super exciting, especially if you think about longer-duration storage and pairing that up with dirt cheap solar and wind. That could be game-changing in a lot of places. So absolutely, it's an area that we're looking at.

David Roberts:

Are there deal announcements coming anytime soon?

Michael Terrell:

I would like to think that you'll see a steady stream coming from us in the near future, hopefully.

David Roberts:

The third pillar is the overall grid, the policy piece. This is something Google just released a new white paper about. Give us a broad overview of the key policies Google has identified that need to shift. The obvious context here is there's only so much Google can do within current regulations and laws, so in some sense, it's going to need help from governments to get to its 2030 targets. Which policies are the key levers?

Michael Terrell:

Before I get to that, I want to go back to the question around why we have set this goal for ourselves of 24/7 carbon-free energy. Part of it is because of policy. What we're finding with companies that had these 100 percent renewable energy goals, us being one of them, is that you can accomplish that simply by finding where renewable energy is the cheapest, buying a whole bunch of it, applying it to your annual consumption, and there you go.

We're all doing this because we're trying to solve for climate change. To do that, we need rapid decarbonization of grids around the world and we need to electrify everything. If you're 100 percent renewable and you're buying cheap renewables, you're not really necessarily driving this grid transformation that we all need to see.

David Roberts:

You're certainly not driving change on the grid where you're located. You might be driving more renewable procurement in those distant dirty grids where you're buying from, but it's the local connection that’s missing.

Michael Terrell:

Another thing we were seeing was in some areas where renewables were really cheap, there was over-procurement of renewables – adding more renewables even when you don't need it, to drive the prices negative.

Again, having companies set these goals and going around the world and procuring is an awesome thing. I don't want to diminish that at all. We've seen incredible progress with that and it's great to see so many companies doing it. But if you're continuing along the journey, this is the next step.

That makes you look at every grid where you operate. I don't think anybody's going to get to 24/7 without the grids themselves getting cleaner too, so it forces you to care about the carbon mix of the grids where you operate. If that mix were to get dirtier, you would like to think that companies will care about trying to make it cleaner.

David Roberts:

As you say, the just-get-to-100-percent-renewables goal has become pretty easy, such that it's low-hanging fruit for a lot of companies now; they can just do it and put a badge on their website and get a little PR boost without undue effort.

Now that you've opened up this next level of ambition, a level of ambition that companies cannot just sit back and do easily, it forces their engagement – because, as you say, to reach the goal requires help from other companies and other jurisdictions and governments.

What's the balance in the corporate sector of companies that were perfectly fine just dumping a little money on renewables and getting the badge vs. companies like some executives I’ve talked to over the years who want to do more? Did you find there was a lot of pent-up appetite for people wanting more ambition?

Michael Terrell:

It's a great question. First of all, I think there are a lot of companies that would take issue with you saying 100 percent renewable is easy. It's still really hard for a lot of them. A lot of companies have thousands of stores or operate parts of their business around the world, so it's hard to do. At the same time, if you're focused on solving this problem and true decarbonization, then it gets you to this next step.

One thing we need to think about as we think about corporate standard setting and greenhouse gas protocols is, what sort of actions do we want to be incentivizing? Is it better for a company to be 50 percent carbon-free globally across all its operations, or is it better to be 100 percent renewable? I don't know the answer to that.

But I do think sometimes there's a little bit of a push to be able to check a box and say “yep, we're clean.” These are hard problems that we're trying to solve, and there's no shame in talking about how hard it is to solve them. I applaud a company that goes from 10 percent to 30 percent carbon-free over a period of time as much as I do one that's reached 100 percent renewable. Everybody's on their own journey, and we want to encourage action.

David Roberts:

One thing you want to do is align incentives so that you get more kudos for efforts that make more of a difference. With 24/7 carbon-free, it's a big jump in ambition, a big jump in difficulty, but is it a big jump in kudos? Is it worth it for an average company? Does the public even know what it means to hit this goal? It seems like part of the effort has to be education, that it's a big achievement, and people get celebrated for hitting it.

Michael Terrell:

We need the standards and those who monitor what companies are doing to focus more on real meaningful actions instead of box-checking. There's a big discussion around that right now, and we should be having it. What signals do we want to be sending to companies? To me, companies have such an amazing ability to drive transformation in the markets, and they intersect the economy in so many different ways. If you can get them to lean in to their strengths, and find ways to innovate through the things that they're already doing, that is going to ultimately drive more reductions over the long haul.

David Roberts:

Have you done research on what the public thinks? Does the public know what to make of 24/7?

Michael Terrell:

I'm not so sure they knew what to make of 100 percent renewable, or when we pledged to go carbon neutral in 2007. At the end of the day, we care as a company about getting to the right place. And yes, the reward system for companies needs to be set up in a way to drive the right behaviors. That's certainly a conversation that we're part of and we want to be part of. But at the end of the day, we're driving toward a North Star which is to get this company decarbonized as fast as possible and hopefully take the systems along with us.

David Roberts:

That brings us to policy. What are the top-line items that Google is calling for with this new white paper?

Michael Terrell:

The overarching lesson here is that you have to have smart policies to drive transformation in energy. We all know that. I think we also know that there's no silver bullet, that you need a comprehensive set of policies to get us there. That's what our paper was trying to accomplish – to identify all of those pathways that we think are going to be necessary to get grids to carbon-free.

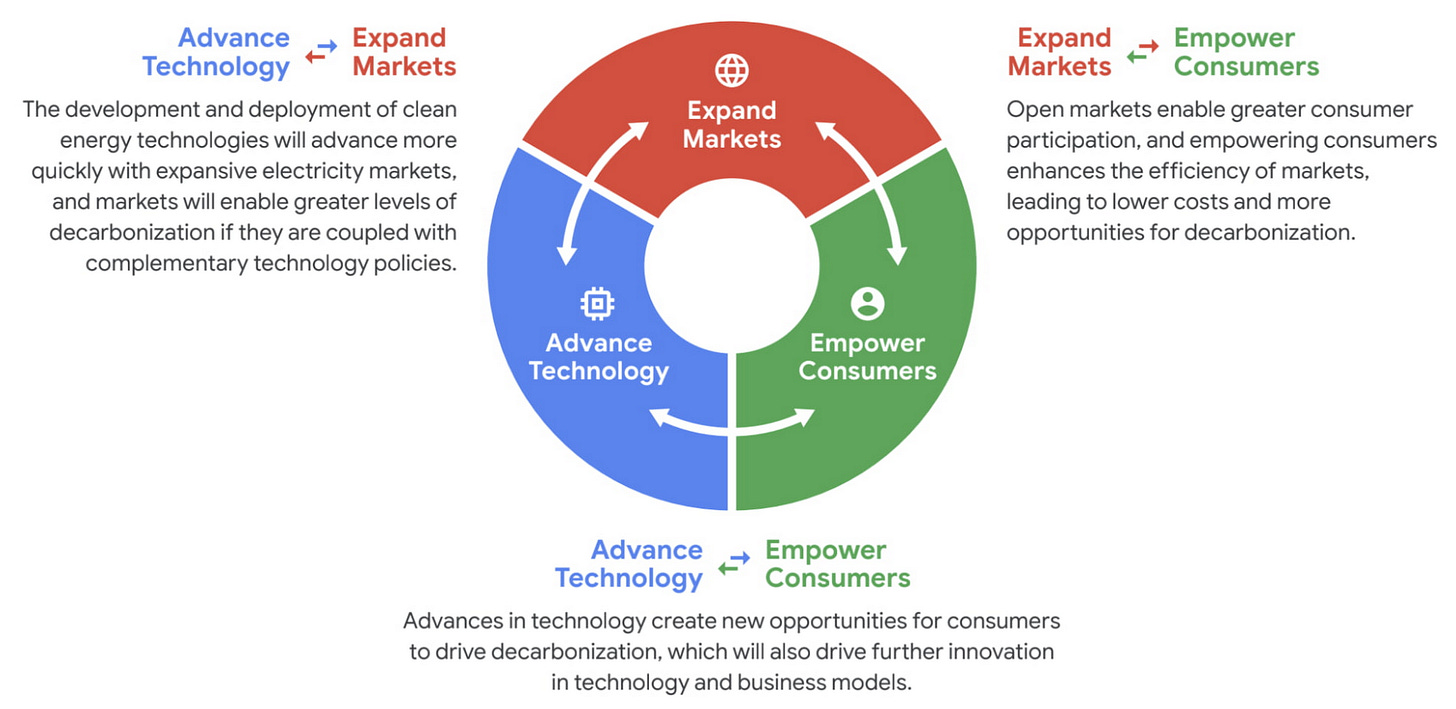

We really think of it in three different ways. The first is, how do we advance the technology? How do we get wind and solar to scale (for example, through clean energy standards)?

How do we take the newer technology through the development process, through R&D policies? How do we expand and design markets in a way that drives decarbonization? That gets to regional market design and valuing the flexibility that you can have with managing demand better.

Lastly, how can we empower consumers? How can we give everybody a direct path to purchasing clean energy? How can we have more transparency in the data and the systems in which we operate?

Those are the three big buckets, and there are many, many things you can do under each that we laid out in our paper.

David Roberts:

On the first piece, technology development, one of the most effective policies is tax credits. There's a big package of tax credits sitting somewhere in some vault (I picture like the giant vault at the end of Indiana Jones), a big package of tax credits from the Build Back Better Act that allegedly everybody's willing to pass and yet no one seems to be passing. This seems particularly like an area where some loud voices from the corporate sector might be welcome at this point – which is a long-winded way of asking, are you up in DC lobbying to get this friggin Build Back Better over the finish line?

Michael Terrell:

Absolutely. We've made multiple public statements on getting those measures through and getting them passed. We regularly meet with stakeholders in DC and on the Hill.

But the thing is, it takes more than just signing on to letters. We were a founder of an organization called the Clean Energy Buyers Alliance; I chair the board. That's companies across many sectors – GM, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Walmart – and that group has come out in support of a 90 percent clean energy grid in the US by 2030, regionalized energy markets. We're trying to build the policy capability of this organization and getting these companies more involved in it, because it really does take building a broad base of support, and that's certainly something that we're strongly working to do.

David Roberts:

When you approach partners in those coalitions, do you find pretty broad agreement on policy? It used to be that everybody was obsessed with carbon taxes, but lately, things seem to have shifted; everybody's into this industrial policy of clean energy standards and tax credits. Do you find that people are mostly on board with that? Or is there a lot of education and wrangling about policy?

Michael Terrell:

They're mostly on board with it; they just don't know how or what to do. One of the things we're trying to provide for companies is a way for them to get involved – a roadmap for advocacy. Again, it gets back to recognizing that policy advocacy is an important part of every company's sustainability journey, and we have to find ways to recognize good work and good efforts there.

But it's a relatively new thing for major companies, getting involved in these clean energy policies. We've been doing it for years at Google. We were lobbying in Taiwan years ago to create a path for companies to go and buy renewable energy directly, and we were working to create programs in places like Georgia and North Carolina. Most companies are not involved at that level, but I think they're enthusiastic and supportive of getting more involved. They just don't know how to do it.

David Roberts:

There's some organization around 24/7, too, isn't there?

Michael Terrell:

That's right. We have created a compact with the UN that's basically a mechanism for companies and organizations to sign on to take the pledge to reach 24/7 carbon-free energy, and then it shares tools and resources with everyone who signed on to help them get there.

David Roberts:

Is there a lot of international interest?

Michael Terrell:

Yes. It's getting a lot of momentum, no question.

David Roberts:

The other policy recommendation piece is about markets. The big looming question that everybody in the energy world is slightly obsessed with is whether there's going to be a Western market, whether the Western states are going to get involved in some sort of RTO. For those who don't know what this means – good God, it's complicated. But basically, most of the country now, I think two-thirds of ratepayers, are in states that are involved in regional wholesale energy markets, and the West legendarily doesn't have one. There's a California RTO, but there's not one that spans Western states. I wrote a long article about this for Vox years ago and it seemed like there was momentum, but I haven't heard a ton about it since then. How are you getting involved in that and what's your read on the appetite for it?

Michael Terrell:

Establishing these markets is incredibly important. For the layperson, it's essentially managing the power grids across multiple states. When you do that over a larger area, it allows you to manage the variability associated with wind and solar, it delivers efficiencies to the system, and it also gives companies more of a direct path to go and contract for clean energy themselves. We have these markets in some parts of the United States but not others, and they're incredibly important. If I could name a top five list of things I'd like to see, this would be on the list.

David Roberts:

Are all of your high-performing plants in areas with markets?

Michael Terrell:

Absolutely. If you look at all of the corporate renewable energy buyers and purchases that have been made in the United States, 90 percent of them are happening in these regional wholesale markets or deregulated retail markets, and only 10 percent are happening in vertically regulated markets. So it's incredibly important.

We've been working hard on this. But if I could have my pick between the West or the Southeast, I would create one of these in the Southeast. I want both, but the southeastern US is really a set of balkanized utility grids. We've been working hard with advocates down there to try to get an RTO established in the Southeast. We've had legislation introduced in the Carolinas and made a lot of progress, but we still have a long way to go.

David Roberts:

Southern utilities are legendarily, let's say, not on board with all this. I’m curious what your reception is down there.

Michael Terrell:

I don't know why they wouldn't be on board with delivering savings to all of their customers, because that's what these markets do. We're making progress. These regional markets are super important to reaching deep decarbonization. The two areas of the country that are lacking them are the western United States and the Southeast, and we're working on both.

David Roberts:

The Southeast just passed some sort of quasi-, semi-, little bit of a market thing.

Michael Terrell:

It sounded like a lot more than it ultimately was. It was really a proposal to allow the utilities to trade some power over the borders, but it wasn't going to create the full wholesale market that you want to see created.

David Roberts:

New markets are great. Of course, lots of people have lots of different complaints about how existing markets operate, as well. Are there particular wholesale market reforms that you have your eye on?

Michael Terrell:

There's a long and wonky list of reforms that I won't bore you with. All of these markets could work better. The big thing we need to learn how to do is to value all of the attributes that either a demand-side program or a generation technology bring into the market.

For example, if I run a large program that cuts demand, can I treat that as a virtual power plant and bid that into the market? Can that get valued in a certain way? Are we valuing clean energy resources the way that we should relative to others? Are we valuing clean energy resources that also are firm and dispatchable – baseload, so to speak – the way we should?

There are reforms like that that could improve the regional markets. But the most important thing is, we should have regional markets in every part of the United States. No question.

David Roberts:

I'm curious about your engagement, if there is any, with state regulators, the public utility commissions of the world. One of the things I hear from reformers in the electricity world is that these PUCs have their hands on an enormous amount of the nation's emissions, on enormous levers of change, but they rarely come in for much scrutiny or examination. Most of the meetings are sparsely attended. It's this ripe area where a little bit of intervention seems like it could have a big effect. Are you in dialogue with state PUCs?

Michael Terrell:

We have a team that has people in every region that engages within these forums. I've gotten to spend quality time in places like Des Moines, Iowa and Oklahoma City talking to commissioners and testifying before commissions on these very issues. You're exactly right – they play a huge role in charting the future course of the electricity system.

I will say that they're only as good as the laws they operate under. It's the overarching laws, which in many cases are decades old and outdated, that really set up the structure in which the systems operate, so those need to be changed as well. DC gets a lot of attention, but these state and regional policies are just as important, and there's a lot of work that can be done there. Again, getting back to what companies can do – my favorite thing to do is to actually go talk to “red state” governors about the investment that we want to bring to their states and the work that we want to do on clean energy. You can win a lot of converts that way. What we need are more companies delivering that message.

David Roberts:

One other often overlooked fulcrum for change in this area is FERC. When you were talking about trying to allow virtual power plants in markets or trying to get different kinds of resources valued based on their different attributes, that brings to mind FERC. FERC just allowed some of these distributed energy resources in markets. Are you engaged in FERC proceedings right now? Is that an area of scrutiny for you?

Michael Terrell:

Yep. We're part of business coalitions, we have members of the team that engage in FERC, and FERC policy is just as important. One message I would stress is that energy policy is climate policy. Establishing RTOS, or improving RTOS, or improving state regulatory policies to promote more clean energy – those can have huge benefits to the climate. We've made a lot of progress on energy policy in the last 10, 15 years. It also has more opportunity for broader-based bipartisan support. These are areas that we think are really important.

David Roberts:

As you mentioned, the third piece is empowering consumers. One of the big stories about the current grid evolution is the dispersion of generation and storage and energy resources generally such that the grid edge is full of these resources that need coordination. This raises problems for grid operators, trying to get visibility into all these things, but it also is an area where consumers are directly involved. I'm curious whether you have particular thoughts or policies you'd like to see reformed particularly around distributed energy resources.

Michael Terrell:

The important element here for us is, any consumer, whether it's a residential consumer or a company or a big corporation, should have a direct path to clean energy if they want it. The climate crisis is severe enough that we need to be enabling people to move as fast as they want to get to a carbon-free future.

In practice, that means enabling people to put solar panels on their roofs or allowing companies to have direct access into purchasing from large utility-scale assets. It's all of those things across the board.

There are a lot of barriers to customers and companies doing that right now, and there's a lot of easy things we can do to remove those barriers. Does it increase the challenges with managing the grids? Of course. But is it possible to manage the grids in the wake of all that? Absolutely. You're seeing places do that now. So we really need to remove those barriers.

David Roberts:

Managing highly dispersed, small-scale resources and coordinating them across regions and everything seems very information-heavy, software-heavy, coordination-heavy; it seems like the kind of thing that Google ought to be all up in not just as an advocate, but as a participant. Are you at work on products in that area?

Michael Terrell:

From our perspective, we look at these problems, and we see them as infinitely solvable. The changes that we're seeing happening with the electricity system are much less severe than changes you've seen in other industries that have been completely transformed in the past 10 or 20 years. So yes, we can manage all of this. Can we help? Possibly, and we're looking into that, but there's plenty of room for lots of folks to develop solutions. And you're starting to see that. There's a lot of exciting things happening.

David Roberts:

Indulge me as I play the cynic for a few moments. There's a long history in the sustainability area of greenwashing. I think there used to be a lot of very empty greenwashing, and now, at the very least, there is a vanguard of companies that are genuinely engaged in this.

But when it comes to lobbying and policy – if there were a bill on the floor of Congress to break up Google's search monopoly or force it to separate search from email, something that threatened Google's core business model, we can all envision how Google would react to that. It wouldn't just be issuing statements and signing on to coalitions. It would be in DC, throwing money around, throwing elbows around, twisting arms, blitzing.

I guess a lot of people in the sustainability world wonder, when are we going to see that? When are we going to see these companies in DC acting as though this is a core issue? It's easy to sign on to things and call for things.

How do you address a cynic? Do you feel like Google has got skin in this game in a way that is new?

Michael Terrell:

It's a fair question. It should be the next evolution in corporate sustainability. We all recognize that policy is going to be absolutely crucial to solving for climate change, so why are we not measuring companies against their work in that space? We've been at it for quite some time, but we could be doing more, just like everyone else. We need to be finding ways to encourage companies to do that and showing them the way to do that, because it can be a very strong force for positive change in the space.

We’ve certainly seen that in some of the work that we've done around clean energy in places like Asia and the US states. We're trying to build up the capabilities so companies can get more involved in DC through CEBA and other groups like that. But I'd like to see more, and we should see more if we're serious about solving this problem.

David Roberts:

I'm sure there are aspects of this that you could not have anticipated when you first announced this 24/7 goal. In the two years you've been pursuing what's necessary for this, are there things you have learned that were unexpected? Are there difficulties that were unexpected? Are there things that were easier than expected so far? It's still early in the process, but what’s surprised you so far?

Michael Terrell:

The benefit is having a goal that fundamentally solves the problem, and we need more of those goals. The time for interim steps and measures is over. We all need to be orienting ourselves toward, what are the things that we fundamentally have to change to solve these problems? If you're 20 or 30 or 40 percent there instead of 100 percent toward a halfway measure that checks the box, that might be a better place to be, but orienting ourselves toward really driving the changes in the economy that we need to change is something that we all need to do.

I think we’ve been somewhat surprised at what we’ve seen as we embarked down this road of all the areas we didn't think to look or weren't looking at because we weren't trying to fundamentally solve the problem. Not thinking about how electricity demand relates to supply; not thinking about certain regions of the world and saying “oh, we'll just deal with those later”; not dealing with certain facets of our business; not thinking about policy in the way that we should. The lesson on 24/7 is really, can we all get more focused on the real problems that we have to solve and work together to try to solve them? Because we don't have a lot of time, and we need to be moving much faster.

David Roberts:

My optimistic take on all this is that once we start looking and trying, we have a pretty consistent record of finding out that things move faster than we think, are cheaper than we think, and are easier to solve than we think. As you say, pursuing that 24/7 goal gets people looking in places they hadn't looked before; I think they're going to find a bunch of tools that they didn't even know they had. There are going to be ways to get at this that we don't even know about yet.

Michael Terrell:

Tying it back to my tenure at Google, the benefit of being here as long as I have is that I've gotten to see things happen that we thought were absolutely impossible. I never thought we would see electric vehicles scale the way that they've scaled. I never thought that we would be doing solar deals in the southeastern US that are cheaper than what's on the grid. I never thought that we would be procuring renewable energy at gigawatt scale. But we're doing all of those things now.

A couple of years ago, 24/7 seemed completely like a moonshot and something that's not possible, and I can promise you that pretty soon here, we're going to be showing that it is possible. So there's a lot to be discouraged about in the world, especially on the policy side, but there's also a lot to be encouraged about. I'm certainly excited for the future, and I think we're entering a period where we're going to see a lot more of this kind of change, which is exciting.

David Roberts:

These are interesting times, on all sides. Thank you so much for coming on, and thank you for your work over the years on this. It's been fascinating to follow.

Michael Terrell:

Thanks for having me.

Share this post